Andrew

Kotting’s 1996 film, Gallivant,

charts a ragged journey around the entirety of Britain’s coastline. Parallels

could be drawn with the psychogeographic impulse of Iain Sinclair (who has

worked with Kotting and written on his films), or the films of Chris Petit and

Patrick Keiller. However, where Sinclair itches with an underground literary

neurosis (all occult alleyways and hidden districts, writers and places

feverishly constellated as steps are taken and retaken along the overlooked)

and Keiller’s Robinson films wryly

observe a kind of flat documentation (I have yet to see any Chris Petit, but

Sinclair’s essay ‘Big Granny and Little Eden’ persuasively draws them all

together as a generation of filmmakers that were reinvigorating a way of

seeing/travelling Britain), Kotting is a more mischievous and bounding

presence. The film is a lovingly stitched home video where both travelogue and

diary are spun into a hand held odyssey: at once poetic and absurdist, itching

with energy and yet accommodating the possibilities of an essay film (Chris

Marker’s Sans Soleil was an important

touchstone for Kotting). Pockets of contemplation appear without thesis, pagan

giants and sword dancing twist into lugworms and washing lines, there is no

time for the bland coherence of any one singular thread – all is fraying and

brought together, unrelated but somehow speaking.

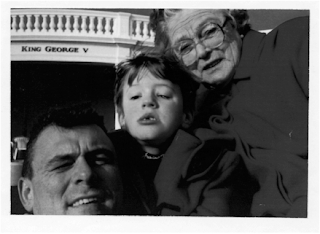

It is

an improvised journey, restlessly awake to the ‘happenstancial’ of chance and accident;

zipping through lanes in a camper van and led with boisterous humour and energy

by Kotting himself, bringing together his 85-year-old grandmother Gladys and

his 7-year-old daughter Eden in a madcap trip that explores generational and

geographical distance but never succumbs to sloppy metaphor. Where and when

proximities bridge and blur the distance of miles or years, Kotting’s film

eagerly jumbles its strands in a bricolage of communities, landscapes and

conversations, held together by the film’s driving cohesion: the growing bond

between Gladys and Eden. This is a relationship that incorporates and extends

many of the film’s preoccupations: language, age, mobility, change, tradition,

signs…

Eden

has Joubert’s Syndrome, a genetic condition that causes ataxia, sleep apnia,

hyperpnea (abnormal breathing patterns) and (among other symptoms) a

disturbance of balance and coordination. The life expectancy is drastically

reduced, a grim prognosis which Eden Kotting has gone on to continuingly defy.

There is a sense with Gladys, at 85, of a stoic realism in facing the remaining

years that, like Eden, could be cut short in the film’s imagined future: an off

the map kinship that heightens the significance of their travelogue. Yet

Kotting never exploitatively dwells on this, there is no sentimentalism wrung

from their time together and no contrivance of a narrative beyond the journey’s

own circularity. What is brought out

is the fizzing drama and comedy of communication: where Eden communicates

through high pitched monosyllables and a form of sign language, Gladys witters

earnestly or remarks with frank and piercing humour. A family trait.

The

film opens with a man that appears to be standing in front of a weather map, or

a map of England, or both. He appears to be signing as a clipped voiceover

introduces the film in a prologue that adopts the tones of public service

broadcasting.

G A L L I V A N T the title appears as though

glimpsed

etched

lettered

in a window’s grime, found

dirt

on the lens

Throughout

language is unmoored, Eden signs broken sentences, place names appear and

disappear, subtitles suggest ‘mystical thematic threads’ which in turn suggest little

more than the suggesting property of language used in this context,

communicating, trying to point, but as one sign encountered warns, ‘DO NOT

ANCHOR BETWEEN SIGNS’. The man that is seen signing at the film’s start is revisited

later, the camera draws out and reveals his vocal counterpart: “This is the

shabby second hand symbolism of our times that my grandson has been driven

too!”

The

film’s sound is a collage of sampled loops, what sound like the quaint and

informative broadcasts of lost radio stations, or public service messages,

circulating conversations, echoes, Kotting’s own observations, sound effects, cut

& paste relics from bygone transmissions, parodies, pastiche, and the

constant performance of a kind of ‘Britishness” … or, more provincially, a

Queen’s English that seem to grow exclusively around the early BBC…as though

spawned between a microphone and a tea cup, poised between efficient upper

class news anchor and the ‘nudge, nudge, wink, wink’ of a carry-on

travesty…these sounds, these scraps of audio tradition, they all crowd and

swirl in and out of the film’s consciousness –memories that arrive in flurries

to announce their own departure, disappearing allusions, names and artefacts

drawn to obscurity, eroding with the coast –

The

film shifts between 35mm and Super 8 with the giddy wheeling of a child’s

perception (recalling the diary films of Stan Brackhage, or, more contemporary

to Kotting, the phantasmic cut, zoom & paste of Guy Maddin). We are

constantly split between the desire to document and a desire to escape

documentation, into something more unpredictable and reckless. Kotting will

often film someone or something from a relatively conventional stasis, and then

follow up with a more haphazard wheeling of macro sequences… whether it is a

person speaking

“keep away from Swansea on a

Saturday night,

its like the Wild West”

its like the Wild West”

“I

think about dying a lot”

“what

happens after –

“You

don’t see the Welsh on TV

“Who

the fuck is Gladys?”

“The

tide always goes out

dunno

where it goes

but it always comes back.”

“you

can fuck off back down South”

“The

only thing I hate is a thunderstorm, thunderstorm and mice”

“My hat is a

tea cosy –

“ –

on a day like this you can almost hear the ghosts…”

or

playing an accordion in Grimsby as the tide begins to swill around muddied

shoes: the camera first observes, and then, as if unable to hold back any

longer, Super 8 dives into close ups and a frantic barrage of textures,

colours, skin, bristle, thistles, bees, tongue…all but forced into the mud of

each moment… calling out its character into a tactile frenzy of detail.

allotments,

terrace housing, burial grounds, makeshift football pitch, power plants,

bridges, upturned boats, tent, camper van, kite, beach, sky, clouds, sea, sun,

jumping, water, surf, blown foam, hillside, grass, condensed milk, how to say,

how to say, heritage? can you ken John

peel, left, left to “pure chance”, shattered ankle, layabouts, government,

countryside, roadside, smoke, housing, box, cube, rust, hand on tiller,

graffiti on the pavilion, laughter, water, time-lapse, “Dadda”, postcards,

public toilet, 99 flake, “in London they’re all too busy”, pagan, gurning,

fish, red coat, bucket and spade and and

and

Lindisfarne:

Eden runs toward the

camera, her movement all the more triumphant and free having earlier witnessed

the milestone of her first unaided steps, and now she is armed confidently with

a bucket and spade, Gladys is in the background flying a kite, everything is

slowed down, the beach opens up

“One

imagines some of the earliest experiences

of

two small children

the other an

old person

near the end

of her life

They

leave you the feeling there’s nothing more to be said –

There

they all were, in the warm sunshine”

Towards

the end of the shared voyage, Kotting pushes for an eccentric alliance between

Gladys, Eden and himself and three oddly chosen symbolic figures. The mundane

hi-vis and glamourless stalwart of road safety, the lollipop lady, is fetishized

and made to become an ambiguously elevated model of quaint Englishness…or

simply an appealingly comic uniform and another strange tradition. Gladys is benighted

in lollipop lady garb. The Virgin Mary has accompanied their winding journey in

the form of a small figurine tacked to the dashboard. In this eccentric

alliance, Eden dons the religious cloth. Meanwhile, as Kotting himself

frequently insists – much to the confusion of interviewees – he is the monk.

This unholy trinity of travel: Lollipop, Mary and Monk are united, to what

purpose and for what reason, remains necessarily unclear. This is ritual,

dress-up and performance cut loose from any corresponding contours of

recognisable belief – it is a playful refusal to ‘ANCHOR BETWEEN SIGNS’ and to

celebrate that unresolved territory as its own ‘gallivant’.

This is where the

film’s charm exists, as an infectious adventure

picked

up and turned over

spit,

wind and soil,

broken

bones

and

words failing

but

trying

scavenged along shorelines

pieced

together, joyously

taken

apart

between

people and landscape and the memories of both

where

the proud public toilet seeks a plaque

in

the friendly collision

dirt

splash and "daft as they make 'em"

as

unpretentious as a dead fish

and buoyant, carrying

forward

(armchair

held aloft, silhouettes

hold

hands towards

John O’Groats

going

on and on

over

the moors

sun

setting

making

the

verve of happening happen

the

film is

as

the journey

imagined

with

the strength

of agile

improvisation,

keen-eyed,

open

the fun

fooling

between

affirming and defiant

where perspective is

shared between

the very old and very young

‘populated by the old, the timeless

and

the anachronistic. It belongs

to

the iconography of the seaside.

Pensioners

queuing

For the

Spring Serenade,

Grandchildren

milling around

Waiting

for Rod Hull and his Emu’ – A. Kotting